Tiny Phonon Laser Could Revolutionize Future Smartphone Designs

Engineers from the University of Colorado Boulder and Sandia National Laboratories have developed a breakthrough in smartphone signal processing. Their innovation replaces bulky radio-frequency filters with a tiny, integrated phonon laser. This new technology could eventually make future phones more efficient and powerful.

The discovery, published in Nature, shows how sound waves—rather than light—can be harnessed on a microchip. While still experimental, the approach promises to simplify how devices handle wireless signals.

Current smartphones rely on dozens of surface acoustic wave (SAW) filters to manage radio signals. These components sit on separate chips, taking up space and adding complexity. The new phonon laser changes this by generating precise acoustic waves directly on a single chip.

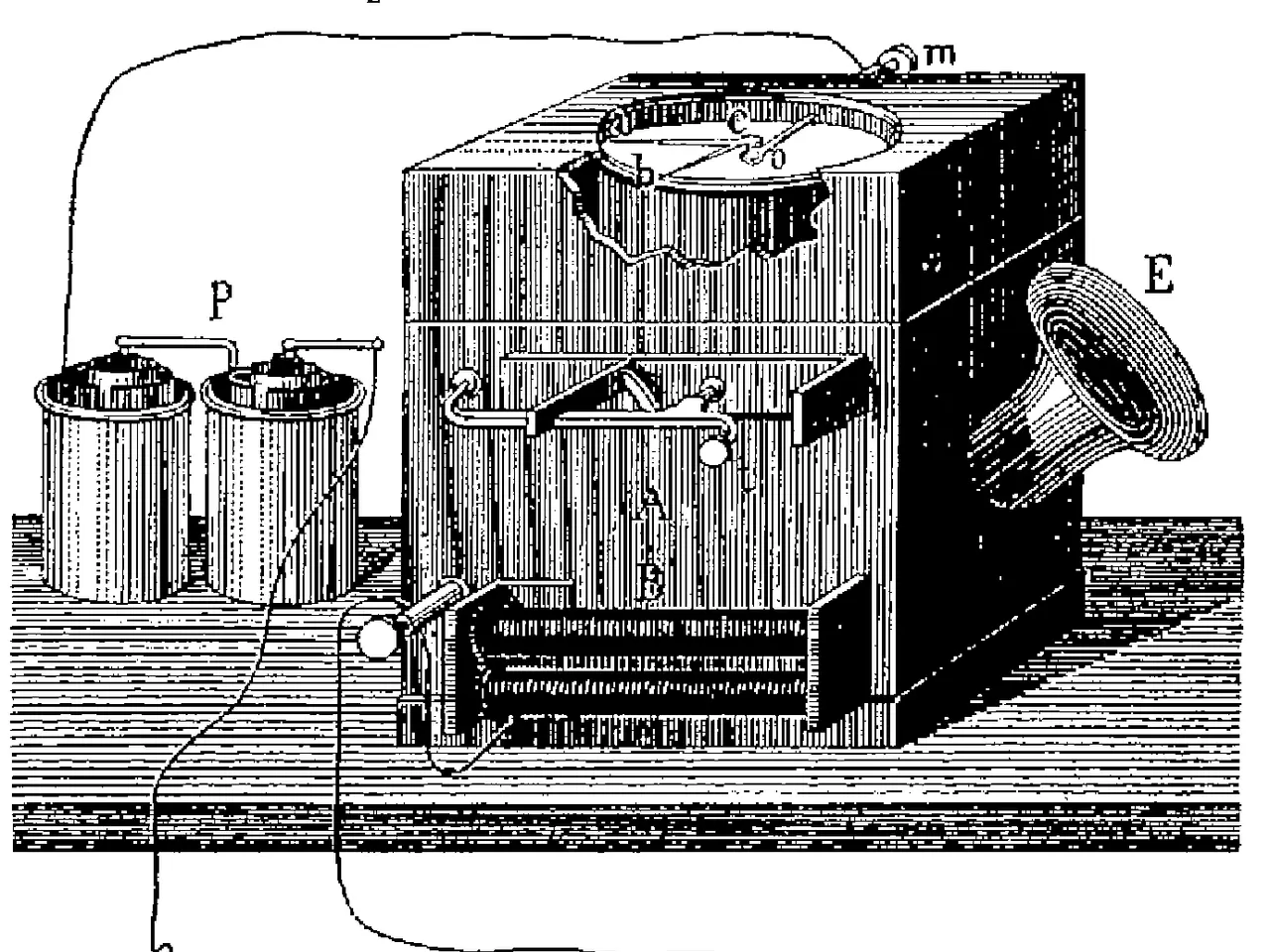

The device works like an optical laser but amplifies vibrations instead of light. Its layered structure includes a silicon base, a lithium niobate layer, and an indium gallium arsenide layer that acts as the gain medium. This setup allows it to produce high-frequency sound waves (up to 100 gigahertz) while using less energy than traditional SAW filters.

Researchers describe the work as a proof of concept. They have shown that acoustic amplification can be controlled and integrated into standard chip manufacturing. However, challenges remain before the technology reaches consumer devices. Scaling up production, ensuring energy efficiency, and keeping costs low are key hurdles.

The study does not provide a timeline for when phonon lasers might appear in commercial smartphones. For now, the focus remains on refining the physics and overcoming practical barriers to mass adoption.

The team's findings suggest a future where radio signal processing happens entirely within a phone's main chip. This could reduce size, improve performance, and cut manufacturing complexity—if the technology matures beyond the lab.

The phonon laser represents a step toward simpler, more efficient smartphone designs. By replacing multiple external filters with a single integrated component, it could streamline production and enhance device capabilities. However, further development is needed before this experimental technology becomes a standard feature in everyday phones.

Read also:

- Executive from significant German automobile corporation advocates for a truthful assessment of transition toward electric vehicles

- United Kingdom Christians Voice Opposition to Assisted Dying Legislation

- Democrats are subtly dismantling the Affordable Care Act. Here's the breakdown

- Financial Aid Initiatives for Ukraine Through ERA Loans