India's Supreme Court bans instant triple talaq in historic women's rights ruling

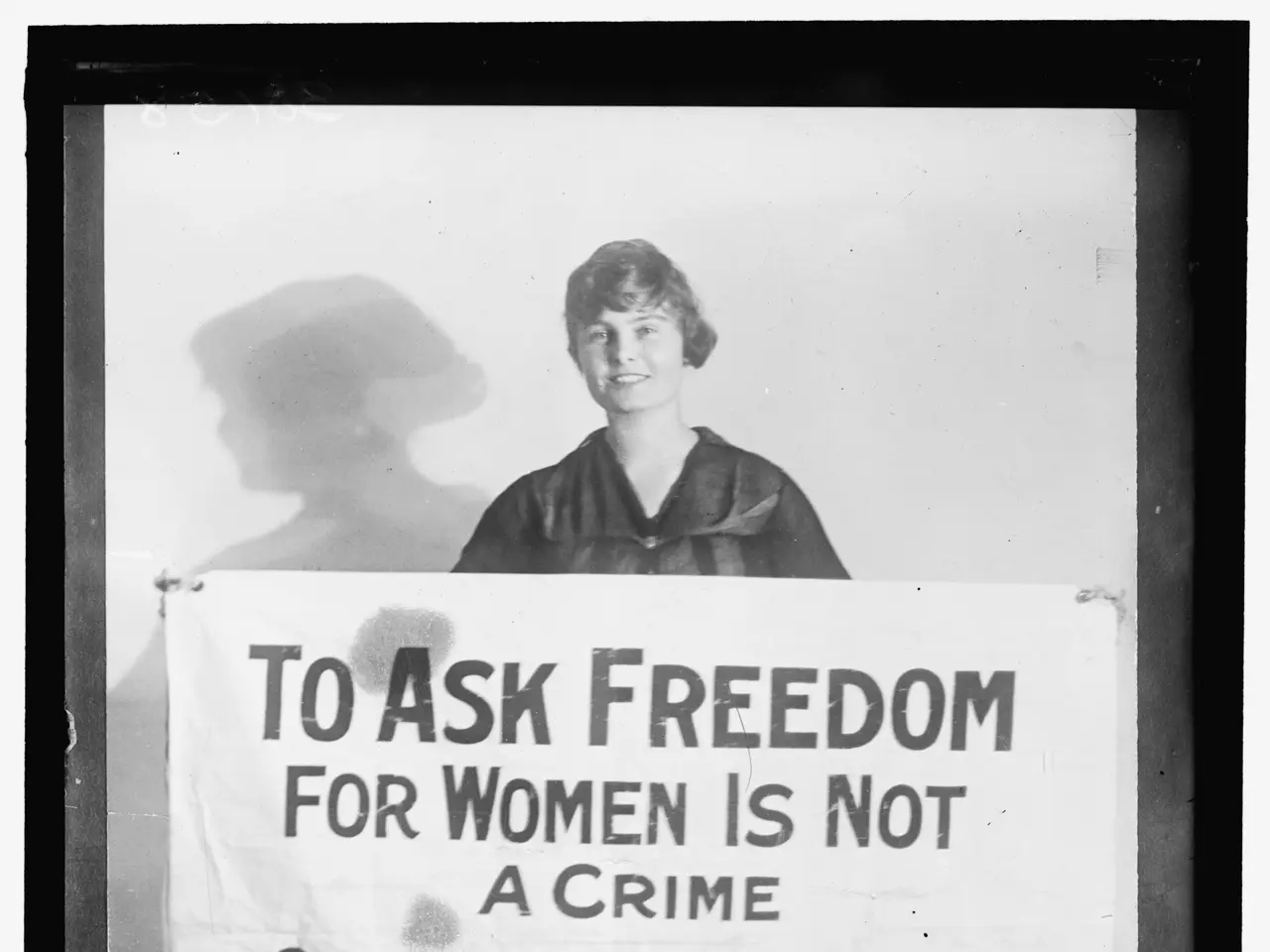

In 2017, India's Supreme Court delivered a landmark ruling on instant triple talaq, a controversial divorce practice in Muslim personal law. The case, brought by Shayara Bano, challenged the legality of her sudden divorce and reignited debates on gender equality within religious customs. The verdict marked a turning point for women's rights in the country.

The dispute began when Shayara Bano petitioned the court after her husband divorced her through instant triple talaq, a practice allowing men to end marriages by uttering 'talaq' three times in one sitting. She argued that the custom violated fundamental rights under Articles 14 (equality), 15 (non-discrimination), and 21 (dignity) of the Indian Constitution. Her legal challenge questioned whether personal laws could be exempt from constitutional scrutiny.

The respondents, including religious bodies, defended the practice as an essential part of Islamic tradition protected by Article 25, which guarantees freedom of religion. They also claimed that personal laws fell outside judicial review. However, the Supreme Court examined whether the practice aligned with constitutional principles.

In a split decision, the majority of judges ruled that instant triple talaq was unconstitutional, calling it 'manifestly arbitrary' under Article 14. Justice Kurian Joseph went further, declaring it invalid even under Islamic law itself. A minority opinion, while upholding the practice, urged Parliament to regulate divorce through legislation.

The ruling did not alter the Muslim Personal Law Application Act of 1937 in other countries like Pakistan, Bangladesh, or Indonesia, where similar legal systems exist. Yet, it triggered wider discussions on gender equality in Muslim family laws across South and Southeast Asia. By 2026, no binding reforms had followed in those nations, but the case remained a reference point in debates on religious practices and women's rights.

The 2017 verdict set a precedent by affirming that constitutional values of equality and dignity extend beyond religious boundaries. It dismantled a practice that left Muslim women legally vulnerable and expanded the scope for challenging discriminatory personal-law customs. The decision also highlighted the tension between judicial intervention and religious autonomy in India's pluralistic legal framework.

Read also:

- Executive from significant German automobile corporation advocates for a truthful assessment of transition toward electric vehicles

- United Kingdom Christians Voice Opposition to Assisted Dying Legislation

- Democrats are subtly dismantling the Affordable Care Act. Here's the breakdown

- Financial Aid Initiatives for Ukraine Through ERA Loans